The 1929 Magnitude 7.2 "Grand Banks" earthquake and tsunami

Location and Magnitude

- Also known as the Laurentian Slope earthquake and the South Shore Disaster

- Local Date and Time: November 18, 1929 at 5:02 pm Newfoundland time

- UT Date and Time: 1929-11-18 20:32 UT

- Magnitude: MW 7.2; MS 7.2; mB 7.1

- Maximum Intensity: Rossi Forel VI

- Latitude: 44.69° N

- Longitude: 56.00° W

- Depth: 20 km

* Now thought to be 28, la Research

On November 18, 1929 at 5:02 pm Newfoundland time, a major earthquake occurred approximately 250 km south of Newfoundland along the southern edge of the Grand Banks. This magnitude 7.2 tremor was felt as far away as New York and Montreal (see isoseismal map of felt area below). On land, damage due to earthquake vibrations was limited to Cape Breton Island where chimneys were overthrown or cracked and where some highways were blocked by minor landslides. A few aftershocks (one as large as magnitude 6) were felt in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland but caused no damage.

The earthquake triggered a large submarine slump (an estimated volume of 200 cubic kilometres of material was moved on the Laurentian slope) which ruptured 12 transatlantic cables in multiple places (locations of cable breaks can be seen as small red triangles on the isoseismal map) and generated a tsunami (a large induced sea wave). The tsunami was recorded along the eastern seaboard as far south as South Carolina and across the Atlantic Ocean in Portugal.

Isoseismal Map

All intensities are reported according to the Rossi-Forel scale. Intensities record the effects of earthquake shaking and do not represent damage caused by the tsunami.

Seismologists at Canada's Dominion Observatory determined the original intensity values by sending questionnaires to local postmasters (here's a sample intensity questionnaire response from Lewisporte, Newfoundland). Data took weeks to collect and months to interpret. Today we are able to produce similar intensity maps within a day or two of the earthquake through the many on-line reports filled out by the general public on our "Did you feel an earthquake?" page.

Recent examination of the 1929 reports provided revised earthquake shaking intensity values for localities in eastern Canada and the United States

Tsunami devastates the Burin Peninsula, Newfoundland.

Approximately 2 1/2 hours after the earthquake the tsunami struck the southern end of the Burin Peninsula in Newfoundland as three main pulses, causing local sea levels to rise between 2 and 7 metres. At the heads of several of the long narrow bays on the Burin Peninsula the momentum of the tsunami carried water as high as 13 metres. This giant sea wave claimed a total of 28 lives - 27 drowned on the Burin peninsula and a young girl never recovered from her injuries and died in 1933. This represents Canada's largest documented loss of life directly related to an earthquake, although oral traditions of First Nations people record that an entire coastal village was completely destroyed by the tsunami generated by the year 1700 magnitude 9 Cascadia earthquake off the coast of British Columbia. More than 40 local villages in southern Newfoundland were affected, where numerous homes, ships, businesses, livestock and fishing gear were destroyed. Also lost were more than 280,000 pounds of salt cod. Total property losses were estimated at more than $1 million 1929 dollars (estimated as nearly $20 million 2004 dollars).

Extent of damage from the 1929 tsunami on Burin Peninsula, Newfoundland (modified from Whelan, 1994). Village names in bold indicate where lives were lost.

Photographs

Most of the photographs are courtesy of the Provincial Archives, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador (PANL). Click on the thumbnail images for larger images

PANL image A 2-149

The home of Steven Henry Isaacs of Port au Bras, which was towed back to shore after being swept out to sea by the tsunami and anchored to the fishing schooner Marian Belle Wolfe

PANL image A 2-146

Remnants of a destroyed dwelling, Port au Bras.

PANL image A 2-147

Cleanup along the shore. Note the masts of a submerged sailing ship in the bay, possibly the Port au Bras harbour. One such vessel was refloated and able to resume fishing the following season.

PANL image A 1-141

PANL image A 1-145

PANL image A 2-150

Destroyed remnants of coastal homes, businesses, wharfs and fishing gear.

Buildings in Lord's Cove tossed and smashed by the tsunami. Photograph by H.M. Mosdell, from the collection of W.M. Chisholm

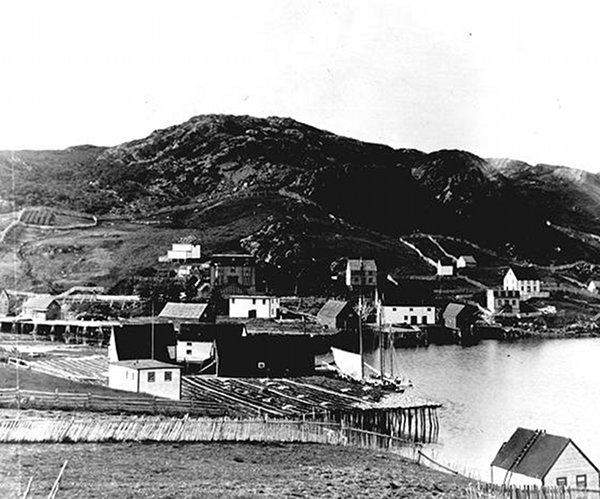

PANL image B 6-109

Burin harbour before the tsunami, circa 1920

Burin Relief supplies prepared in front of 241/243 Duckworth Street, St. John's during the winter of 1929/30. Photo from Collection 137, No. 739 at the centre for Newfoundland Studies Archives, Memorial University of Newfoundland

While the wave smashed and destroyed many buildings, it simply lifted others off their foundations and floated them away. One general merchandise store, 9 x 17 metres, was moved 60 metres inland and deposited in a meadow, with all its stock left intact on the shelves.

People took to the remaining boats in search of people hanging to debris or trapped in floating homes. In one such home rescuers discovered a sleeping baby, whose family had been drowned on the first floor. A man, swept to sea, swam to another floating house only to find it was his own. The house was later towed back to shore and replaced on its foundation.

The ferocity of the wave was not restricted to the land; it also tore up the seabed. This destruction of the seabed was believed by many Newfoundland fishers to be the dominant factor in poor fish catches during much of the Great Depression. The poor catches seem to be the result of a failure of the bait fishery. This failure involved three species of the open seas (herring, squid and caplin) and has proved hard to pin on the tsunami and its disruption of the nearshore and shoreline sediments.

The day following the tsunami a winter storm moved into the area, dropping temperatures and adding sleet and snow to the survivors' misery. The provincial capital of St. John's and the rest of the world did not immediately know of the devastation caused by the tsunami. The only telegraph line from the Burin Peninsula had, coincidentally and unfortunately, gone out of service just prior to the earthquake. When word did get out, help came quickly. The S. S. Meigle was dispatched from St. John's with a relief committee of the government, doctors and nurses and arrived at Burin on the afternoon of the November 22. Long before the coast was reached wreckage was met, mute evidence of the disaster which had befallen the region. Recovery assistance was also provided by the Red Cross and British and American governments.

Here's a brief exerpt from the November 27, 1929 account from Hon. Dr. Mosdell aboard the Meigle, as reported in the St. John's TheDaily News (Lost At Sea) - "Dwelling houses were reduced to a condition reminiscent of wartime description of the effects of heavy shell fire. Former sites of gardens and meadows now thickly strewn with boulders, some of them as large as casks thrown upon the shore by the devastating force of the tidal wave. Motor boats, stages and wharfs piers lifted bodily and thrown far inland in heaps of ruins. Lord's Cove and Lamaline visited by the relief expedition yesterday here dozen of houses, stores and stages were found thrown bodily into the pond at the head of the harbors, huddled together in one heap of destruction. Some lay upright but half submerged while others lay on their sides, and still others were entirely overturned."

Newspaper accounts and images

A sampling of what the country's newspapers were saying about the 1929 earthquake and tsunami

Research

The 1929 Laurentian slope earthquake, along with the 1933 Baffin Bay magnitude 7.3 event indicate that large earthquakes along Canada's eastern continental margin are not uncommon. The new year 2005 National Building Code accounts for the expected level of earthquake shaking from a similar earthquake anywhere along the length of this margin. Although the Grand Banks earthquake occurred only 75 years ago, the general feeling in the scientific community is that similar tsunami-generating earthquakes are very rare.

Adams, John and Stavely, Michael, 1985 Historical Seismicity of Newfoundland Earth Phyisics Branch Open File 85-22

Adams, John and Wahlstrom, Rutger, 1995 Revised Seismicity of the Grand Banks and Offshore Newfoundland Geological Survey of Canada Open File 3043

Bent, Allison, 1995 A Complex Double-Couple Source Mechanism for the MS 7.2 1929 Grand Banks Earthquake Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, v. 85, no. 4, p. 1003-1020

Ruffman, Alan, 1996 Tsunami Runup Mapping as an Emergency Preparedness Planning Tool: The 1929 Tsunami in St. Lawrence, Newfoundland Geomarine Associates Ltd., Contract Report for Emergency Preparedness Canada, Office of the Senior Scientific Advisor, Ottawa, Ontario, 399 pp.

Ruffman, Alan and Hann, Violet, 2006 The Newfoundland Tsunami of November 18, 1929: An Examination of the Twenty-eight Deaths of the "South Coast Disaster". Newfoundland and Labrador Studies, Memorial University, St. John's, NL, v. 21, no. 1, p. 97-148

Soulsby, Richard, Smith, David, and Ruffman, Alan, 2007 Tsunami Reconstructing Tsunami Run-up from Sedimentary Characteristics - A Simple Mathematical Model. Sixth International Symposium on Coastal Sediment Processes - Coastal Sediments '07, May 13-17, New Orleans, Louisiana. Volume 2, pp. 1075-1088.

Tuttle, M.P., Ruffman, A., Anderson, T., and Jeter, H., 2004, Distinguishing tsunami from storm deposits in eastern North America: The 1929 Grand Banks tsunami versus the 1991 Halloween storm. Seismological Research Letters, v. 75, no. 1, p. 117-131

1929 "Grand Banks" Earthquake and Tsunami Links

Not Too Long Ago ... Seniors tell their stories First hand accounts from the Seniors Resource Centre, St. John's Newfoundland - pdf document

Geological disasters in Newfoundland and Labrador Geological Survey of Newfoundland and Labrador

Coastal flooding Newfoundland and Labrador Heritage

History of Nova Scotia 1920-1939 Nova Scotia's Electronic Attic

Tsunami Links University of Washington